Introduction:

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint in which the ball (femoral head) articulates with a socket (acetabulum). Normally, the socket is deep and cup-shaped.

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip’ (DDH) is a condition in which the socket fails to develop normally and is shallow like a saucer. It occurs with a frequency of 1 in 1000 live births.

This leads to instability of the hip joint. This instability may be of varying severity:

• Dysplasia: The socket is shallow, but the ball is still within the socket.

• Subluxated: The ball is partially outside the socket.

• Dislocated – The ball is completely outside the socket.

Risk factors for DDH:

Factors that increase the risk of a child having DDH include:

• Breech position: When the baby is delivered legs first instead of head first

• Family history: When either one of the baby’s parents had suffered from DDH during childhood, their baby is 12 times more likely have DDH.

• Intra-uterine overcrowding: This can occur in cases of twin pregnancy, oligohydramnios and uterine malformations.

• Unsafe swaddling practices: Cultures where babies are swaddled after forcible holding the hips in extension have higher incidence of DDH.

• DDH is much more common is girls, eight out of every ten cases of DDH are seen in baby girls. Six out of every ten cases are seen in first born children.

Signs:

DDH is painless. Hence it very often goes undiagnosed in infancy unless a child is specifically examined for it.

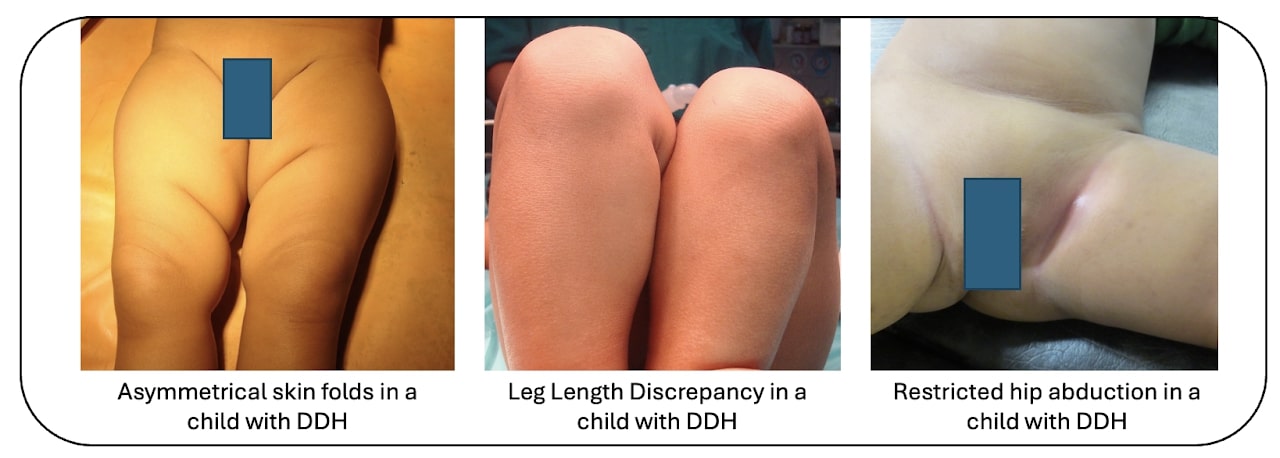

Asymmetric thigh skin folds may also be noted in unilateral DDH. Parents may also note leg length discrepancy in unilateral DDH with the affected leg being shorter than the normal leg.

In infancy, parents may note tightness and difficulty in spreading the hips during diaper change.

However, many times these early signs are missed and suspicion of an abnormality is usually raised only when the child starts to walk.

The child walks with a limp with leaning over from side to side while walking.

Diagnosis of DDH is confirmed in children smaller than 4 months by performing an Ultrasonography. In older children, an x-ray is sufficient to confirm the diagnosis.

Late sequelae:

Dysplasia of Hip is painless during childhood. However, if it remains untreated, as the child grows older, the abnormal walking puts a strain on other parts of the body. Eventually, they develop pain in the back and knees.

Treatment:

Treatment for Dysplasia of Hip is simpler the earlier it is done. Older children require more complicated surgeries and have poorer results.

Treatment of Dysplasia of Hip depends on the age at which it is diagnosed.

Up to 6 months:

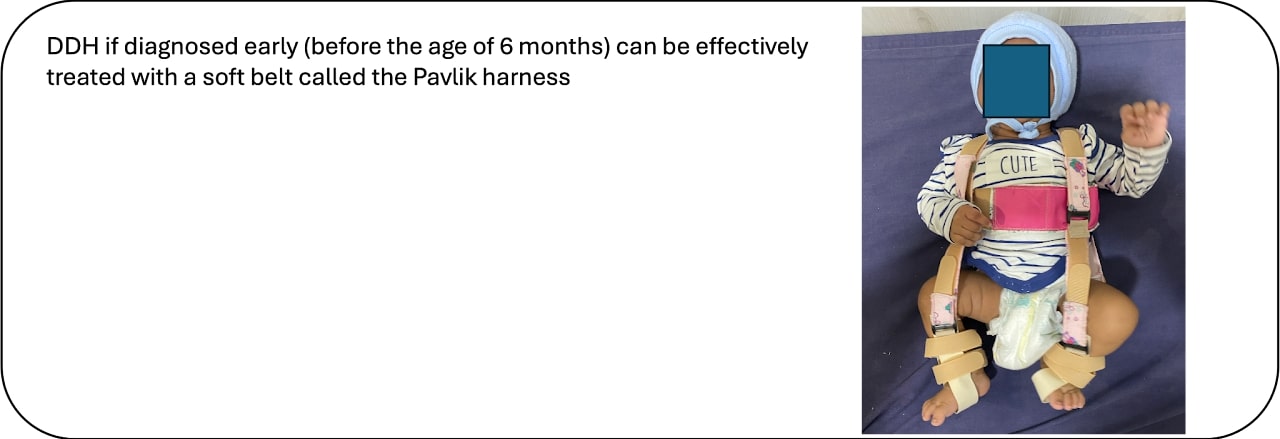

In infants this small, treatment consists of a brace known as a Pavlik harness. This is a soft brace made of fabric, that is fastened into position with Velcro straps.

It acts by gently keeping your baby’s legs in a position that allows the hip to get back into the joint.

The brace is very easy to apply. And quite comfortable, as your baby is free to kick and move around in it. You can also change your baby’s diaper and clean him while the brace is in place.

For treatment with the Pavlik harness to be successful, it is very important that you keep it applied all the time. Repetitively removing and re-applying the brace is an important cause for failure.

During the initial few weeks, the brace must be worn 24*7. Your doctor will get repeat sonographies of the hip done, with the baby in the harness, usually once in one or two weeks, until the hip joint is back in position and stable.

After this, he/she will advise you to reduce the number of hours in the brace gradually over a few weeks until it is discontinued completely.

If treatment with the Pavlik harness is unsuccessful, your baby may need to be treated as for slightly older children (see below)

Older than 1 years:

In children older than 1 years, open reduction is usually necessary. In this, with your child under anaesthesia, your surgeon will make an incision in the groin and open up the hip joint.

He/she will then see what is stopping the hip from getting reduced, usually tight muscles, joint capsule and fibrofatty tissue which occupies the empty acetabulum. These obstructions are removed and the joint is reduced.

Often the joint reduces but does not remain stable, because the shape of the femur or acetabulum or both are abnormal.

In such cases, the surgeon will cut the femur and change its direction and/or cut the acetabulum and make it deeper.

After this surgery also, a hip spica cast is applied, usually for two months.

The above is only an outline to the approach to treatment of a child with DDH. Actual treatment depends on many factors and not just the age of the child.